Category

Ante Meridiem (before noon)

Make something that would be used in the morning

Entrant

Sigi Jade aka Rose Taillor of Worcester (tentative name)

Entry

In praise of clean linen – The Linen Smock

Research and justification

What is the very first thing a medieval woman man or woman would reach for in the morning? Their linen smock or shirt. Linen smocks/chemises/shifts were the standard undergarment for European women right up to the 19th century.

Having an easily washable layer between your body’s oils and dirt and the expensive and difficult to launder outer clothing was considered hygienic and practical. This was particularly relevant in an age where regular washing of the body with soap and water was rare, lest it open the pores of the body for foul humours to enter.

The linen shift could be changed as often as the wearer could afford; this being seen as key to societal acceptance “else thou would’st stink above ground like a beast.” (John Taylor). Linen was particularly good for this; due to its sweat absorption and heat regulating properties.

This shift was accompanied by stockings tied about the knee, and a coif as head covering. This layer was essentially a permanent barrier between the person and the outside world, and, at least according to John Taylor, was a garment to evoke titillation and respect.

“Yet hath a smocke this great preheminence (Where honour’s mix’d with modest

Innocence)

It is the Robe of maryed chastitie,

The vaile of Heauen-belou’d Virginitie,

The chaste concealemēt of those fruits close hidden

Which to unchaste affections are forbidden,

It is the Casket or the Cabinet where Nature hath her chiefest Jewels set:

For what so ere men toyle for, farre and nereby sea or land, with danger, cost, and feare,

Warres wrinkled brow, & the smooth face of peace

Are both to serve the Smocke, and its encrease.”

In general, women made and mended the linen undergarments for their families, even the wealthiest woman sewed these most garments. Anne Boleyn was said to be very upset when she learnt that Henry VIII’s wife, Katherine of Aragon was still mending his shirts, despite the fact he had sidelined her for Anne by then. This emphasises the intimacy inherent in the act of sewing the layer closest to one’s skin.

Extant linen undergarments are rare, likely reflecting that they were used until they fall apart, then used as rags, and eventually, tinder “But how can we have fire at our desire, Except old Linnen be to tinder burnd.” (John Taylor, 1624).

Indeed, Ruth Goodman suggests that old linen may have been used as sanitary items, given how old linen increases in absorbency and softness over time.

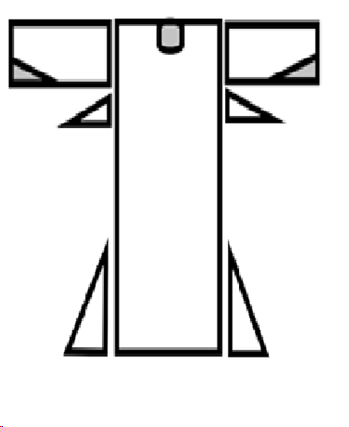

During my research for this project, I realised most of the suggested tutorials are based on older (17th – 18th c) patterns. However, garments constructed by rectangles, squares, and triangular gores are well known (see Herjolfsnes finds) so it makes sense that undergarments share that construction. Given the fabric saving nature of this construction method, and the relative cost of fabric in this time, this further lends evidence to this construction method.

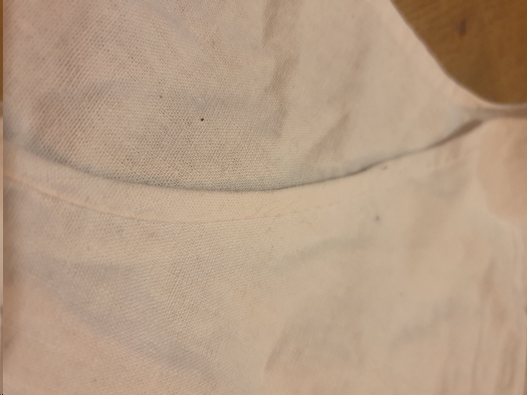

Given my desire to have shifts that could work for different outfits and eras, I wanted to avoid anything with gatherings or collars, as that firmly plants the garment in the latter part of the period, so this neckline was out. My target period was England between the 14th – 16th centuries (I like to float around eras for my garb). The fact I could feasibly create a shift that would work across a 200-year time period reflects how little this garment has changed over the years.

I figured that, much like today, it would be acceptable to wear older fashions, so even this older style shift would work for lower class Tudor styles, despite fashionable Tudor styles of shift incorporating a gathered collar and smocking.

Sewing

I cut everything to a much slimmer fit than the patterns and measurements commonly suggested online for this. My body width measurement ended up as my half bust measurement +2 inches + ½ inch seam allowance either side. The armpit gussets were cut out from the end of the sleeve, so the sleeve tapered towards the wrist, starting at the elbow. The side gores started around about the hips, and were as wide as the sleevesFor all my square pattern pieces, I used the thread pulling technique to ensure I was cutting a perfectly straight piece. This took forever, but was immensely satisfying.

I planned to use linen thread, but I like to use size 10 sharps, and the only linen thread easily available to me (Gutteman) was too thick to fit through the tiny eye of those needles. So I opted for a cotton thread instead.

I used small backstitches for the long seams, a running backstitch for the gores which wouldn’t be under tension, and flat- felled the seams with a whip stitch. The neckline, sleeve edge, and bottom hem were all whip stitched.

I sewed the side gores with bias abutting straight grain to minimise stretching, and let it hang for a few days before squaring off the hem and finishing it.

I cut it to maximise fabric conservation, but this resulted in a scandalously short shift. I found some linen scraps, and decided I’d piece them onto the body shifts. It’s rather unsightly, but it now covers my knees! And after-all ‘piecing is period!

References

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1274830/smock-unknown/?carousel-image=2014HB4447https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O110103/smock-unknown/

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O356815/shirt-unknown/

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O78791/smock-unknown/

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O78791/smock-unknown/

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O327719/shift-unknown/

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O82638/dolls-shift-unknown/

https://awanderingelf.weebly.com/blog-my-journey/beyond-the-aprondress

File:Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry juin.jpg – Wikipedia Limbourg brothers (Dutch, fl. 1385-1416). June, Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, 1412-1416. Tempera on vellum; 22.5 x 13.6 cm (8.9 x 5.4 in). Paris: Musée Condé, Ms.65, f.6v.

Ruth Goodman, How to be a Tudor, : A Dawn to Dusk guide to Tudor Life. Penguin Books. 2016.

“The Praise, of Cleane Linnen. With the Commendable vse of the laundresse” John Taylor, 1624.